5.1

Cancer is a type of disease in which a group of cells shows one or a succession of three properties: uncontrolled growth, invasion, and sometimes metastasis. These three malignant (virulent, dangerous) properties differentiate cancer from benign (harmless) tumours, which are self-limited and mostly do not invade or metastasize. Most forms of cancers form a tumour but some, like leukaemia, do not.

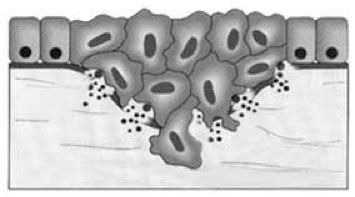

Cancer originates in cells, the building blocks that make up tissues, which in turn make up human organs. Normally, cells only generate new cells when the body needs them. When cells grow old, they die, and new cells take their place. Sometimes, this natural process goes wrong, and new cells form even when the body does not need them, or old cells do not die when they should. This is what is referred to as uncontrolled growth.

The second malignant property, invasion, is when a tumour has formed due to uncontrolled growth and invade surrounding tissues. This property enables the cancer cells to move into a lymph (most common) and blood vessel and be transported through the body, possibly establishing a secondary tumour. The creation of this distant tumour is the third malignant property of cancer cells, the metastasis.

Once cancer cells spread, they are often found in the lymph node. But cancer can spread to almost any other part of the body. The most common places where cancer spreads to are the bones, liver, lungs, and brain. These new tumours, that are a result of metastasis, have the same kind of abnormal cells and the same name as the original tumour. For example, if cancer spreads from the spleen to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually the same cancer cells as were originally found in the spleen. The disease is thus called metastatic splenic cancer (coming from the spleen), not lung cancer.

Uncontrolled growth

For more reading:

→ National Cancer Institute

→ Cancer basics

→ Pinkribbon

Cancer risks with dogs

5.2

Cancer is one of the leading cause of death in dogs. It is estimated that at least 1 in 3 domestic dogs will develop cancer and die of it.

All dogs are at risk when it comes to cancer, but no one knows what exactly causes certain types of cancer – other types might be better understood. Vets and researchers often cannot explain why one dog develops cancer and another does not. Research has shown that dogs with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop cancer.

Some risk factors are:

-

Hereditary (genetic): If our dog’s ancestors have developed cancer, then our dog has a higher risk of developing it himself.

-

Early neutering: Some studies have shown a correlation between the neutering of bitches before the first heat and the development of certain cancer types. However, early neutering also protects the bitch against the risk of mammary cancer. So the risk has to be weighed against the benefits.

-

Nutrition: some believe that industrially produced food (dry or wet) might favour certain types of canine disease, among others cancer. However, there is no scientific proof yet.

Further reading:

Der Jahrtausendirrtum der Veterinärmedizin

http://www.transanimal-editor.de/index_d_jahrt.htm -

Pollution and exposure to toxic substances (cigarette smoke, car fumes, garden herbicides, insecticides...). There are studies from the UK which have shown that dogs who spend several hours a day on a highly fertilized lawn develop a certain type of cancer.

Resouce and further reading:

http://www.dogsnaturallymagazine.com/lawn-chemicals-and-cancer-in-dogs/ -

Our dog’s age. Age is the biggest risk factor: The risk increases with age. 76% of older dogs who develop cancer had no other risk factors.

-

Our dog’s breed. Certain breeds seem to have a slightly higher risk than others for developing a certain type of cancer (see below …)

German Shepherd Dogs, Golden Retrievers, Boxers, Great Danes, English Setters and some other large breed dogs are particularly predisposed to developing certain forms of hemangiosarcoma. Short-haired dogs, like Whippets, Dalmatians, Pointers, Greyhounds and Pit Bulls are also predisposed. The reasons for these breed associations are not well understood, but they do suggest a genetic component to this type of cancer.

Resource and further reading: http://www.petwave.com/Dogs/Health/Hemangiosarcoma/Symptoms.aspx -

Our dog’s general health: dogs who are overweight, obese or sedentary seem to have a higher risk of developing cancer.

Many risk factors can be avoided; others, such as family history (genetic factors) and age, cannot. We can try to protect our dogs by staying away from known risk factors (see list above) whenever possible, but we shouldn’t let this dominate our and our dog’s life. It is important to keep in mind that not all dogs who have known risk factors get cancer, and that, on the other hand, not all dogs developing a cancer have a family history of the disease. In fact, except for growing older, most dogs diagnosed with cancer have no clear risk factors.

Whether our dog has one of the above risk factors or not, we want to be sure to detect a possible cancer early enough. Therefore, we should discuss this concern with our veterinarian as soon as possible, when the dog is still young. He or she may be able to suggest ways to reduce the risk factors (weight, nutrition …), and can plan a schedule for regular check-ups and screening. Be sure you have a good insurance policy for your pet which will cover screening and, if necessary, treatments (see chapter 14).

Further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancer_in_dogs

5.3

Cancer diagnoses in dogs are unfortunately on the rise, as are cancer diagnoses in people. In fact, canine cancer is the leading cause of death in pets, especially over the age of 9 years.

Dogs have greater than 80 percent genetic similarity to humans, versus only 67 percent for mice. Thus, some dog cancers are microscopically and molecularly identical to cancers in people. Similarities in the response to treatment are similar, too. This is good news for canine cancer research.

Many of the genetic mutations that drive cells to become cancerous in people are the same mutations that cause cancer in dogs. In fact, when viewed under a microscope, it is impossible to distinguish between a tumour from a human and one from a dog.

Such similarity can be beneficial to cancer research – for both 2-legged and 4-legged individuals. A field of study known as "comparative oncology" has recently emerged as a promising means to help cure cancer. Comparative oncology researchers study the similarities between naturally occurring cancers in pets and cancers in people in order to provide clues to treat cancer more effectively for both.

Today, most pet dogs receive high-quality health care into old age, and dog owners are highly motivated to seek out improved options for the management of cancer in their companions, and to minimize the side effects.

This means that any new cancer treatments first shown to be effective in humans can frequently be predicted to have a similar benefit in canine cancer patients, and vice versa. Studies on the patient's overall quality of life during treatment (possible positive and negative side effects) can also benefit dog owners, by providing access to promising new cancer treatments for their pets with cancer.

Rescources and for more reading:

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/02/03/health/dogs-cancer-partner/index.html?sr=twCNN020317dogs-cancer-partner0951PMVODtopPhoto&linkId=34115027

.